Non-Fiction

Ponderosa / Juliana Chow

September 2020

Dear ------,

Last week I finally went out to our yard and pulled weeds; some are so common, like the mustard and sour grass you wrote of blooming in southern California, there are weeds everywhere—plantains, dandelions, and thistle—weeds I pulled up in the yard in St Louis where I lived, weeds I pull up in Beaverton, Oregon where I live now. But they give me no sense of the familiar. We left St Louis before the summer humidity began; I missed the fireflies we once chased on night walks in the park, the buzzing whirr and clicks of the cicadas at dusk to which we would fall asleep. Here I’ve seen spiders and their cobwebs in every crevice and dragonflies skimming over water. As we left a weekend camping by a lake at the foot of Mt Hood, smoke from late summer wildfires followed on our heels, back to Beaverton where high winds blew in the smoke hot and dusty. The sky is luminous orange. I am neither of Missouri nor of Oregon. What unbelonging do I traverse now?

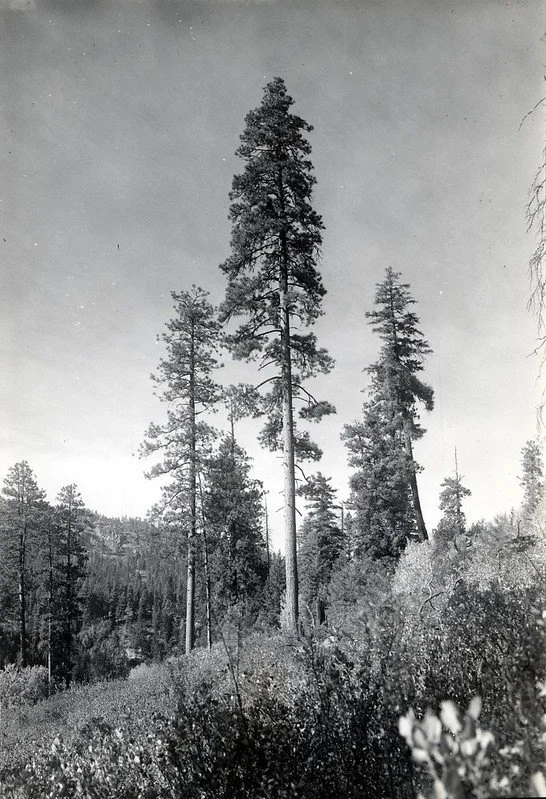

Across the street from where I live is a large Ponderosa Pine that leans and then curves sinuously up to the sky with a pronounced “S” that seems precarious in such a tall species. When we first moved into the neighborhood, the tree seemed out of place. The pine’s long bushy needle bunches gave its relatively narrow frame a shaggy, unkempt look and its curved posture made it look like a slightly off-kilter lone dancer. While other large trees in our neighborhood—oaks, Douglas firs, spruces, and others—cluster together in little stands, this pine is on its own. And in a suburban neighborhood of low midcentury ranch-style homes, the towering trees seem even taller—and lonelier. When I think of the pine, I mostly think of its undulating curve, so uncharacteristic and audacious.

May 2021

Dear ------,

Has a year really passed since we began these letters? A friend from St Louis suggested that I read Alice Munro because she wrote while the sole caregiver of her children, “writing in the stolen time in between for many years.” Interspersing Munro with Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, I have been imagining a series of short stories, the protagonists all versions of myself in nondescript situations à la Eric Rohmer films. Still lives in motion. —A grocery store trip to buy ingredients for a birthday party: gazing at red lettuce, beets, and chard and choosing between 60% or 63% cacao chocolate chips. A terse conversation with a former friend who is now a doctor and posts elaborate food photos including an homage to Hetty McKinnon on Instagram. Selecting plants at a nursery: papaver nudicaule, mimulus guttatus, feijoa sellowiana, ceanothus spp. Screaming in desperation and exhaustion at a 3-year-old child: Why?— The only thing distinctive about them would be the strangeness of a social circle defined by mostly Asian friends surrounded by a larger public world of mostly non-Asian white people. But I am probably lying to say that is the only distinction; it is the only obvious distinction.

To a certain extent I can hardly write about what happens. I am making arrangements of plants, whether they are sensible or not. People are giving away coltsfoot, douglas aster, and thimbleberry, and I try to figure out how to drive over to pick them up in between visits to playgrounds and naps. It is already too late in the spring to really transplant but, I tell them, I am new to gardening. Really I am new to mothering. To escape, I pull weeds and sort river stones out of dirt and mulch. I buy lupine polyphyllus and lavender and gaze longingly at my neighbor’s bursting scatters of eschscholzia californica and artichokes. Can you tell what I am dreaming of? What are you dreaming of?

It took about three months of sleep training for my son to start “sleeping” through the night but it feels like it took three years: three years from when my daughter was born to when my son turned one.

October 2021

Dear ------,

Yesterday we began planting echinacea among the front yard shrubbery and vine maples in the shade of our large oak and spruce trees. I managed to dig out some desiccated boxwoods and C dug holes for two plants before our three-year-old demanded that she needed help changing her wet clothes and our one-year-old needed his nap. Because I suspect that our house is on what used to be an oak savanna, I had decided to splurge on some oakscape plants at a local nursery. There are little 3-inch pots of goldenrod and a rather mottled red currant still to be planted. In the backyard, we will plant thimbleberries, sword ferns, and more fringecups in the shade. I am waiting for you to send me the California poppy seeds so that I can scatter them in the open pockets between the bushes. The days and nights are turning colder and the mornings begin gray more often than not.

A few weeks ago, I saw the boys who live across the way playing outside while I was on a walk. Their parents Marshall and Cat had met during college in Springfield, Missouri; when they first introduced themselves, we were tickled by the coincidence of having moved from Missouri also. Our neighborly chats are warm and friendly but that is the extent of it. The only person I ever see working in their front yard is Marshall, who gives me a silent wave when he is out raking and sweeping the pine needles. Today, though, the boys are out running circles across the grass with plastic Star Wars lightsabers that light up and produce a satisfying “wvmmm” sound.

“Hello there, what are you up to?” The older one is an affable third or fourth grader with dark brown hair and a Harry Potter-ish look that he likes to embellish by affecting a slight British accent when he speaks. His brother, a towheaded kindergartener with a gapped smile, ignores me shyly. From their perch in a wagon, my own children look on with great interest and apprehension. After some pleasantries, I point to something that looks like a flat headstone in front of their tree. “What is that?” I ask.

Harry Potter races to the polished rectangular stone and runs a few turns around the yard and then comes to a halt in front of me. “That says that our tree is Oregon’s Favorite Tree,” he announces proudly. I sidle up a bit further onto their lawn and peek over at it: “Beaverton’s Favorite Tree, 1989.” I look up at the pine in its little circle of flowers surrounded by a spare lawn and almost no shrubs. Pinus ponderosa.

On the Beaverton Tree Inventory map, the Ponderosa Pine is marked “T2” as a “Significant Individual Tree,” only one of three in my neighborhood. Most of the significant trees cluster around the downtown area; I wonder if this is due to foot traffic—that what is most seen by people or the arborists is what becomes “significant.” How does a tree accrue significance? Does it witness a historical occasion or mark a sacred place? Is it a rare species? A quintessential “type” specimen? Did someone simply adore the tree so much they could not bear contemplating its obscurity? Or did the tree survive by sheer indifference for so long that it eventually became prominent, much like the “useless” tree Zhuangzi observed? The tree inventory map is the scattershot of love’s inattention. In an old announcement from 2013 published by Beaverton’s urban forestry department about the pruning of a large downtown Ponderosa Pine, former city arborist Patrick Hoff seemed rather wistful that it took so long for it to receive arboricultural care: “I pushed to have the tree accepted as ‘Beaverton’s Favorite Tree’ when the program was still running nearly 20 years ago. But funding was cut and it never got the recognition it deserved.”

December 2021

Dear ------,

Today we woke to a snow-dusted morning—snow-patched lawns, snow-laden boughs, and rhododendron bushes holding snow spirals on their leaves. I reminded my daughter, whose birthday is on the winter solstice, that she was born on a morning much like this one when the first snow of the winter fell in St Louis and quietly marked a changed world. We drove to Washington Park in search of a hill to sled down but there wasn’t enough snow; the children made snow angels and I made a tiny snow gnome with a leaf as a wide-brimmed hat and bark pieces for its eyes, nose, arms, and buttons. By the afternoon, the snow had mostly melted and when I peeked out the kitchen window at the Ponderosa, it looked the same as always, disappearing beyond the limits of my view, leaning precipitously and waving.

The seeds you sent arrived—one red envelope of California poppy seeds and another of a wild flower mix you indexed as: “lupine / tidy tips / 5 spot / desert bluebelly.” They sit on my bookshelf unopened like bright New Year’s red envelopes that I slide between books and save for early spring. Between part-time work and the rest of the time mothering, I never got around to preparing soil and scattering seeds.

In Finding the Mother Tree, Suzanne Simard describes how she began her research on trees and their forest communities with a fervor after she worked for a logging company. As a young forester assigned to mark clearcut tracts and write up and evaluate planting prescriptions, she saw how the young seedlings of monotonous lodgepole pines planted in place of clearcuts were sickening and dying. She spent years tracking the fungal membranes connecting trees to their neighbors and studying the processes that ferried nutrients and passed chemical signals between them the same way our neurotransmitters do. Her mapping revealed that “the biggest, oldest timbers”—the mother trees—“are the sources of fungal connections to regenerate seedlings...they connect to all neighbors, young and old, serving as linchpins for a jungle of threads and synapses and nodes.”

Beaverton’s Favorite Tree of 1989, are you a mother tree? If you are, where are your seedlings? Who do you talk to on long winter nights? In the Willamette Valley, ponderosa pines were once a common tree species of a pre-settlement oak savanna landscape where white oak grew along with ponderosa pines, Douglas fir, Pacific madrone, bigleaf maple, and Oregon ash. Unlike their kin east of the Cascades, this variety of ponderosa pine was adapted to the rainy winters and dry summers of the valley. How deep and far do a ponderosa’s roots reach? What mycorrhizal fungi might weave its mycelia around them and stretch their filaments into the humus far below, connecting neighboring tree roots? Does the ponderosa lean and murmur to the white oaks across the street? Do they wonder where their children have gone?

You asked me how I am finding time to write when my children aren’t in daycare and my youngest usually wakes around 5am. You asked, of a passage I sent you from Hong’s Minor Feelings: “What is a ‘you’ that is a placeholder for the self? A you that is in motion but not arrived?” (I write to you at a late hour, sacrificing sleep for time’s dilation.) My younger child has been alternately tearful or playful at bedtime and waking frequently at night with a periodicity that becomes increasingly taxing with each new phase. In an attempt to shorten how long he cried, I began to sleep on the floor of his room. I would reach my hand through the bars of his crib and hold his hand until he fell back asleep. When he figured out how to climb out of his crib, I gave up and just sleep on the floor with him in my arms. He is old enough now to be able to shout between screams and cries, very clearly, “Mommy, mommy.” Over and over, I decide I cannot do this anymore. Instead of waking less, he wakes more frequently; and we are all strained from lack of sleep. I can say, quite clearly, that I am not writing for my children though maybe someday it will become

other

wise